Florsheim Shoe Factory History

Landmark Status & Overview

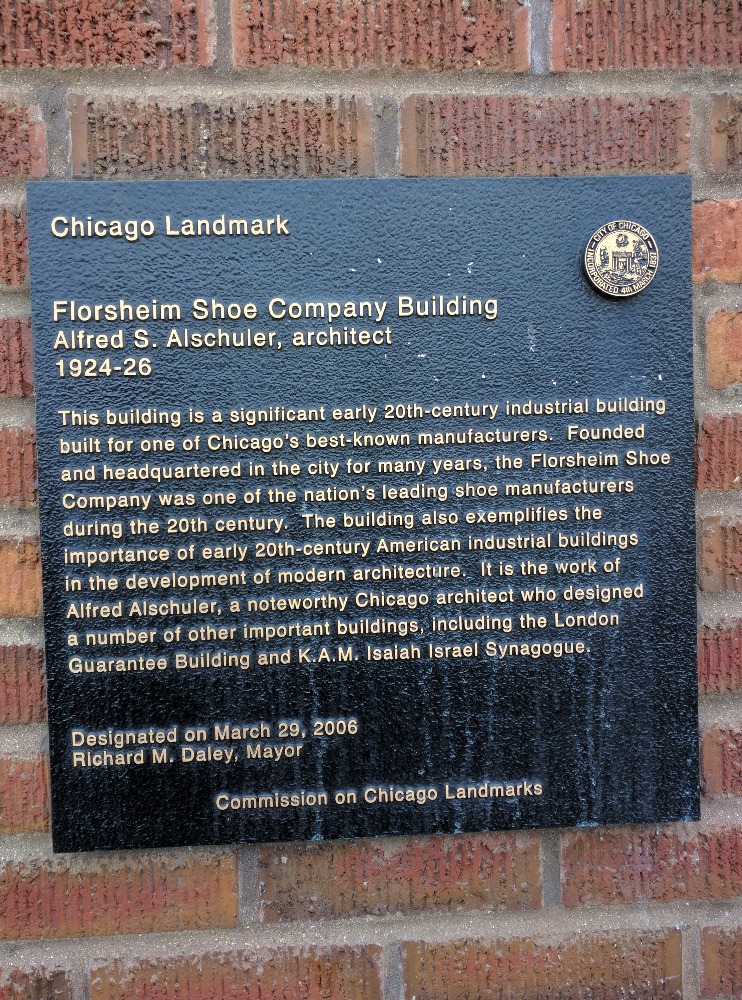

The Chicago City Council granted official Landmark status to the Florsheim Shoe Company Building on March 29th 2006, which over the decades produced millions of pairs shoes that were sold throughout the country.

"The Florsheim Building is one of the best examples of how the design of an industrial building could benefit its use and increase its efficiency," said Mayor Richard M. Daley.

Built between 1924 and 1926, the six-story building at 3963 W. Belmont Ave. is an excellent example of a "daylight" factory, so-called because its reinforced concrete and glass construction allowed for natural light and ventilation.

The building was designed by Chicago-born architect Alfred S. Alschuler, who is famous for his belief that necessary features of industrial design were clear floor plans and natural lighting.

Aschuler's design grouped utilities, stairways, elevator shafts and restrooms in one area, leaving unobstructed floor space that could accommodate manufacturing equipment.

Florsheim & Co. was founded in 1892 by Milton Florsheim, whose father took a job as a shoemaker after settling in Chicago from Germany. The company soon developed a national reputation as the makers of high-quality men’s shoes.

Florsheim shoes were manufactured on the site until 1986, when the building was turned into a warehouse for a records management company.

The Florsheim Shoe Company and Its Buildings

The Florsheim Shoe Company Building was built by one of Chicago's premier shoe manufacturers, whose products were among the best known throughout the United States during the 20th century. The company was founded in 1892 as Florsheim & Co. by Milton Florsheim, whose German-born father Siegmund had come to Chicago in 1862 and become a shoemaker. Florsheim & Co. soon began manufacturing high-quality men's shoes. After making shoes in existing buildings, Florsheim & Co. built its first factory in 1900 just west of the Chicago River on the southeast corner of Adams and Clinton, and by 1910 the company had 600 workers here. This factory received a seven-story addition in 1912. (Both the original building and annex have been demolished, and a portion of the Riverside Plaza office complex now occupies the site.)

Early on, the Florsheim Shoe Company, the name it took in 1908, developed a marketing strategy that placed great strength on name recognition. Florsheim opened its first company-owned store in Chicago's Loop in the Brand Building at 18 W. Jackson, just off State Street, in 1904 (building demolished), but the vast majority of the company's shoes were sold by independent retailers. Typically in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, retailers bought shoes from manufacturers and placed their own store labels on them. Milton Florsheim objected to this, both in terms of personal pride and corporate marketing, and required retailers to sell the company's shoes under the company's label. Through newspaper and magazine advertising, Florsheim developed a national reputation for high quality, and retailers became eager to showcase the company's shoes in their stores.

The Florsheim Shoe Company grew rapidly during the 1910's and 20's, building two new factory buildings within a five-year period. The first, a four-story brick factory, was built at 3927 W. Belmont Ave. in 1919. Almost immediately, the company began planning a much larger factory building (the subject property) immediately to the west on a site facing Belmont between N. Harding Ave. and N. Pulaski Rd. (then N. Crawford Ave.). The Florsheim Shoe Company took out a building permit for the Florsheim Shoe Company Building on March 4, 1924, and the building opened in 1926.

The resulting six-story building was constructed of reinforced concrete that formed a visible rectilinear grid that visually defines the building's exterior. Projecting concrete piers rose unobstructed from a ground-level base of red brick to the fifth- floor roof parapet, where the building was slightly set back with a large sixth-story penthouse. The large structural bays that were possible using reinforced concrete were glazed with large multi-paned industrial windows of metal and glass above low horizontal red-brick infill panels. The resulting design was clean and spare, depending largely upon fine proportion and scale and the contrast of pale concrete piers with deep-red brick spandrels and dark- painted window sash for visual effect.

Although the overall appearance of the building is quite spare, some ornament can be found at key points in the building's exterior. The main entrance facing Belmont is set within a simple low-arched terra-cotta surround embellished with medieval-style quoins and shields. In addition, a long and narrow horizontal terra-cotta plaque above the entrance bears the company's name, "The Florsheim Shoe Co." in pale green letters. The building's projecting concrete piers are subtly ornamented with half-diamond concrete moldings and full-diamond brick-and-tile plaques at the top of the fourth floor. (The corners of the building's rooftop parapets have been rebuilt, removing small original sections of terra-cotta ornament similar to that surrounding the building's entrance.) At the time of the Florsheim Shoe Company Building's construction, shoe manufacturing was an important component of Chicago's industrial might. According to Chicago, The Great Central Market, an overview of Chicago commerce and industry published in 1923, there were 29 shoe factories in Chicago, with more than 4,500 workers producing almost 9 million pairs of shoes per year. Chicago's shoe manufacturing industry was noted as second only to that found in New England, and the industry's national prominence was due to both Chicago's location at the nexus of American commercial rail transportation, easing the logistics of shoe shipments to stores nationwide, and the quantity and quality of leather available due to Chicago's Union Stock Yards and the city's 28 tanneries, employing more than 4,000 workers.

By the end of the 1920's, Florsheim's annual sales were $3 million, and the company had five factories in the Chicago area and 2,500 workers. It also had more than 50 company- owned stores around the United States in addition to the hundreds of independently- owned stores that sold Florsheim shoes. The halcyon economy of the 1920's collapsed after the Stock Market crash of 1929, however, and the resulting Great Depression was a very difficult time for American manufacturing. Florsheim, known for its expensive men's shoes, managed to survive both this decade-long economic downturn and the military-oriented economic recovery brought about by World War II, and was one of the top- 10 shoe manufacturers in the United States at the end of the war. Anticipating increased business, Florsheim opened a new Chicago factory in 1949 at Adams and Clinton, diagonally across from the site of its first factory. (Now altered, this building has been adapted for residential use.)

In 1953, the Florsheim Shoe Company was sold to shoe manufacturing rival International Shoe Company (later Interco, Inc.), headquartered in St. Louis. For many years, Florsheim was International Shoe's most profitable division, with 14 factories and 500 retail stores nationwide at the beginning of the 1970's. During the 1980's, however, most of Florsheim's manufacturing went to plants overseas, as was the trend with United States apparel manufacturing in general. It was in 1986 that the building passed out of Florsheim's control, when the parent company, Interco, Inc., sold the building to Records Management Services, Inc. Interco, Inc. declared bankruptcy in the early 1990's, and in 1994 Florsheim was spun off as an independent company with its headquarters back in Chicago. By 2000, Florsheim retained roughly 10 percent of the market for men's dress shoes. It currently is headquartered in Glendale, Wisconsin, as a unit of Wayco Group, Inc.

Architect Alfred S. Alschuler Alfred S. Alschuler (1876-1940), the architect of the Florsheim Shoe Company Building, was one of Chicago's most prominent early 20 th -century architects. Born in Chicago to German immigrant parents, Alschuler received bachelor's and master's degrees in architecture from the Armour Institute of Technology (now the Illinois Institute of Technology), and also took classes at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1900 he began his professional career in the office of Dankmar Adler, and subsequently worked with both Adler and Samuel Atwater Treat until 1907, when he established an independent practice.

Source: https://archive.org/stream/CityOfChicagoLandmarkDesignationReports/FlorsheimShoeCompanyBuilding_djvu.txt